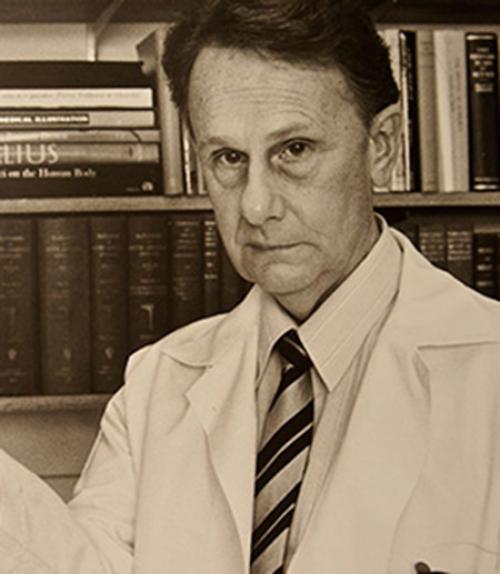

An endowment bequeathed by Kenneth A.R. Kennedy, professor of physical anthropology at Cornell for 41 years, will fund a lecture series and visiting professorship in human evolutionary biology bearing his name.

Kennedy, known for his field studies of early humans and their predecessors in South Asia as well as his work with forensic anthropology, died in 2014 at the age of 83.

“The endowment will showcase Kenneth’s passion for evolutionary biology,” said Jere Haas, the Nancy Schlegel Meinig Professor Emeritus of Maternal and Child Nutrition in the College of Human Ecology and an administrator of the endowment. “He often said that he knew he wanted to be an evolutionary biologist since he was 12 years old. Even during the last few days of his life, he was working on several manuscripts to publish.”

Kennedy and Haas worked together to teach the popular course, Human Biology and Evolution, from the 1980s to 2005, when Kennedy retired. Kennedy also taught popular courses in forensics, which drew students captivated by television shows like “CSI.” Local law enforcement officers also consulted with Kennedy to help evaluate remains, and students would sometimes be invited to participate in those cases, too, Haas said.

The Arts and Sciences Departments of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Molecular Biology and Genetics, and Anthropology are managing the endowment, which totals more than $1 million.

“Kenneth loved the study of human paleontology and evolution. He was fascinated by the stories that could be read from human skeletons,” said Amy McCune, professor and chair of the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “The endowment he has left us will help ensure that Cornell students will continue to be exposed to the study of human skeletal remains and human evolution.”

A committee will finalize the details of the lectures and professorship, Haas said, then seek applications from qualified candidates, probably in the spring. Haas envisions hosting a visiting professor on sabbatical from another institution for a semester or a year, as well as scholars who would visit for two to four weeks at a time to work with students and offer public lectures.

“Dr. Kennedy was dedicated to his students – his personal and heartfelt commitment to his students was evident to all his mentees,” said Anthony Pulgram, one of Kennedy’s nephews. “He worked diligently to advance their scholarship and professional careers.”

Haas said Kennedy would frequently invite students to his home, where he often conducted seminars in his living room.

“Conversations with Kenneth took me through the world of academics to the imponderables of life,” said Laurence Pulgram, another of Kennedy’s nephews. “While he was a leading evolutionist, he was also a faithful Episcopalian, and left his church a stained glass window of St. Thomas Aquinas, the patron of scholars and students, that had previously stood above his desk.”

Kennedy joined the Cornell faculty in 1964. He taught in the Departments of Anthropology, Asian Studies, and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Field studies took Kennedy to India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, England, California and Illinois – almost always with his collaborator and wife of 44 years, Margaret.

“He was devoted to Cornell and enormously grateful for the opportunities the university provided him,” Anthony Pulgram said. “The visiting lecture series will support Cornell and ensure future Cornell students are supported in their studies of human evolutionary biology.”

Kathy Hovis is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.