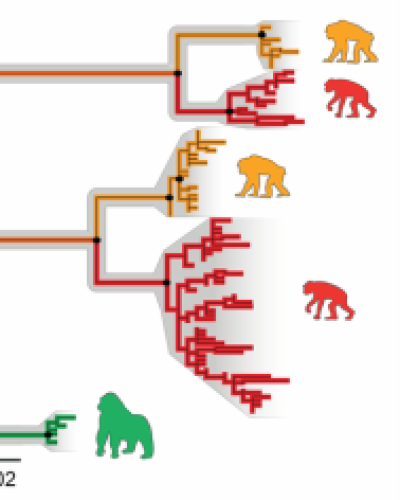

A new study finds that hundreds of bacterial groups have evolved in the guts of primate species over millions of years, but humans have lost close to half of these symbiotic bacteria.

In the study, researchers compared populations of gut bacteria found in chimpanzees and bonobos, our closest relatives, with those of humans – which in total amount to some 10,000 different lineages of bacteria. The scientists analyzed the evolutionary relationships of these bacteria in primates and identified groups of bacteria that were present in distant ancestors of humans and primates. Strikingly, the results showed that these ancestral symbionts are being lost rapidly from the human lineage.

Though the cause of these shifts in human gut microbiomes is not known, the study’s authors suspect changing diets probably caused the divergence.

“The working idea is that the losses we see spanning all human populations, regardless of lifestyle, were likely driven by dietary shifts that happened early in human evolution since we’ve diverged from chimpanzees and bonobos,” said Andrew Moeller, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and faculty curator of mammalogy at the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates, in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, and the paper’s senior author.

In particular, human diets shifted away from complex plant polysaccharides found in leaves and fruits towards more animal fat and protein, Moeller said.

Jon Sanders, a former postdoctoral researcher in Moeller’s lab, is first author of the study, “Widespread Extinctions of Co-diversified Primate Gut Bacterial Symbionts From Humans,” published May 11 in Nature Microbiology. Daniel Sprockett, a current postdoctoral researcher in Moeller’s lab, is also a co-author.

In the study, the researchers analyzed metagenomes, which are assembled by piecing together short base pair sequences from a whole community of genomes; the metagenomes revealed which microorganisms were present in a sample and their relative abundances.

Analyses of 9,640 human and non-human primate metagenomes, including newly generated ones from chimpanzees and bonobos, revealed significant evidence that gut bacteria groups shared an evolutionary history with their hosts, according to the paper.

The results showed that 44% of clades – a group that has evolved from a common ancestor – that have a shared evolutionary history with African apes were absent from the human metagenomic data and 54% were absent from industrialized human populations. At the same time, only 3% of bacterial clades in African apes that did not share an evolutionary history with these hosts were absent in humans.

“This is the first microbiome-wide study showing that there are a great number of ancestral co-diversifying [shared evolution] bacteria that have been co-living within primates and humans for millions of years,” Moeller said.

Still, Moeller highlighted the importance of improved sampling in human populations, especially those outside of industrial countries, in order to fully represent human gut microbiome diversity.

Ancestral bacteria may be passed from one generation to another from mothers to babies, and by social transmission with other members of the same species.

The discrepancy in extinct bacteria between the general human population and those from industrialized countries may point to differences related to modern diets and medicines, such as antibiotics that are known to alter microbiomes. Some researchers have speculated that the disruption of ancestral flora could be playing a role in modern diseases, such as autoimmune disorders and metabolic syndrome.

A second related paper, “Home-site Advantage for Host Species-specific Gut Microbiota,” also led by Moeller and Sprockett, which published May 12 in Science Advances, showed that gut bacteria locally adapt to the hosts they live in, providing a possible mechanism for the long-term stability of these symbioses.

Both papers were funded by the National Institutes of Health.